Since last week, I’ve been reading a few chunks of my book Breaking Together to my Dad, in hospice. That means I must choose the bits that might be worth listening to! One passage tells of an experience at Davos, when I was being encouraged to regard increasing rates of GDP as an evangelical quest. You can hear me read it. The passage is from Chapter 2 on monetary collapse, which you can read in full. The book is also available in all formats and locations.

Subscribe / Support / Study / Essays / Covid

Why Growth Became God

At Davos I thought, perhaps naively, that I was mixing with the real power wielders of the world. I never felt at ease in what Mr Johnston once described as “a constellation of egos involved in massive mutual orgies of adulation.” A few tequilas at the McKinsey Party helped me to ease my awkwardness hobnobbing with people who were often described to me as really-nice-and-down-to-Earth-despite-being-who-they-are. That was the ‘high’ bar that non-famous people tended to set for the people who happen to be billionaires, film stars, CEOs, despots and such like. I learned that the appropriate response was to put on my smile of amazement and say “that’s great.” I had thought it was important that someone like me attended and tried to promote alternative ideas. Some years later, I now know that there have been hundreds of other gullible I-am-different-and-will-make-a-difference activists who tell themselves that story as they maintain fake smiles while listening to absolute garbage coming from one panellist after another and wondering which party to go to next. But at least my years of attending the summits in Davos as a Young Global Leader opened my eyes to a reality of global power. It’s a mess. Most of the people I met with powerful roles seemed incapable of acting competently in the collective interest in accountable ways. Worse, attempts to invite people to think beyond their organisation or ego just seemed to make matters worse.

In one session, where I was sitting in a circle with billionaire tech entrepreneurs and soon-to-be-CEOs of global banks, we were handed cards to encourage discussion. The question we were asked was: “What one thing can I do this year to enable greater economic growth?” The question was explained to us with a reverence, like we were being asked “what one thing can I do this year to help more people find Jesus?” I stared down at the card—a heathen with a thumping heartbeat.

The fact that economic growth became God is one of the reasons why humanity is, to get a bit technical, so exponentially fucked. A quick summary of the basics may help here. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measures the total of the production of all goods and services in a country, and Gross National Product (GNP) measures GDP plus income from foreign investments. Economic growth occurs if GDP rises, after adjusting the figures for inflation. Politicians tell us that such growth is important to us for a number of reasons. They say it reflects improvements in our standard of living, as it means we are accessing more goods and services. They say it also reflects plentiful employment opportunities. They also say it means that as tax revenues increase with growth, better public services can be provided by the government, such as infrastructure, health and education.

Not all politicians have been so enthusiastic about focusing on GDP growth. In 1968, a few months before he was murdered, US presidential candidate Robert Kennedy spoke the following:

“Gross National Product counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl… Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”[i]

Around the time he gave this speech, the environmentalist criticisms of economic growth had been growing in the West. More people were recognising that not only did growth ignore that which is of great intrinsic worth, but it measured much that was not valuable—or even destructive. The deeper critique also existed that growth simply could not continue forever in a world of relatively limited renewable resources like timber from forests, and absolutely limited non-renewable resources such as oil and gas. Ecological damage was already underway in the late 60s, and economic growth was compounding it with frightening speed. That’s because 2 percent growth in any given year is a bigger increase in economic activity than 2 percent growth in the preceding year, because it starts from a larger base. Imagine a blob on the centre of this page that represents the resource ‘footprint’ of industrial consumer society. As it keeps increasing by 2 percent, the amount of surface area it covers expands by a greater amount each year. It would seem to increase slowly but then would speed up in filling the page. And then the room—so there’d be no room for you anymore. That is why we often hear the concern that if an economic system requires infinite growth on a planet of finite resources it will inevitably collapse at some point.

For decades these criticisms were largely ignored by politicians. That changed in 2016 when at last governments began international discussions about the limitations of the GDP measure for either economic or social progress. Even at the World Economic Forum there were earnest discussions about the need for new measures of progress.[ii] Although that was a shift from the growth fanaticism that I had experienced at their Davos summit just a few years previously, there was something completely superficial about their attention to the subject. Economic growth remained their continuing objective for national governments, but it was now combined with additional metrics of wellbeing or environmental quality. Their approach relied upon discounting the deeper critiques of eternal economic growth being impossible by embracing the idea that GDP growth could be significantly decoupled from resource consumption and pollution. This theory is multi-faceted. It includes the view that at the level of individual products, we will be able to get the same for less resource: for instance, a beer can or a car with far less metal needed to make either. Another aspect of the theory is that we will obtain the same function or outcome in our lives without the same amount of resource, because we will switch to consuming a service: for instance, having access to a car, or a bus, rather than owning a whole car to ourselves. Another aspect of the decoupling theory is that the service sector in general provides ample growth opportunities while requiring fewer resources than other sectors such as manufacturing. And yet another aspect of the theory is that there are growth opportunities in the technologies and related products that actually reduce the pollution coming from other activities. All of this together had made quite a powerful and popular theory within the contemporary environmental sector. It offers the vision of a bright green future, which helps make individual efforts within corporations seem worthwhile. The slight problem with this vision is that it is a lie.

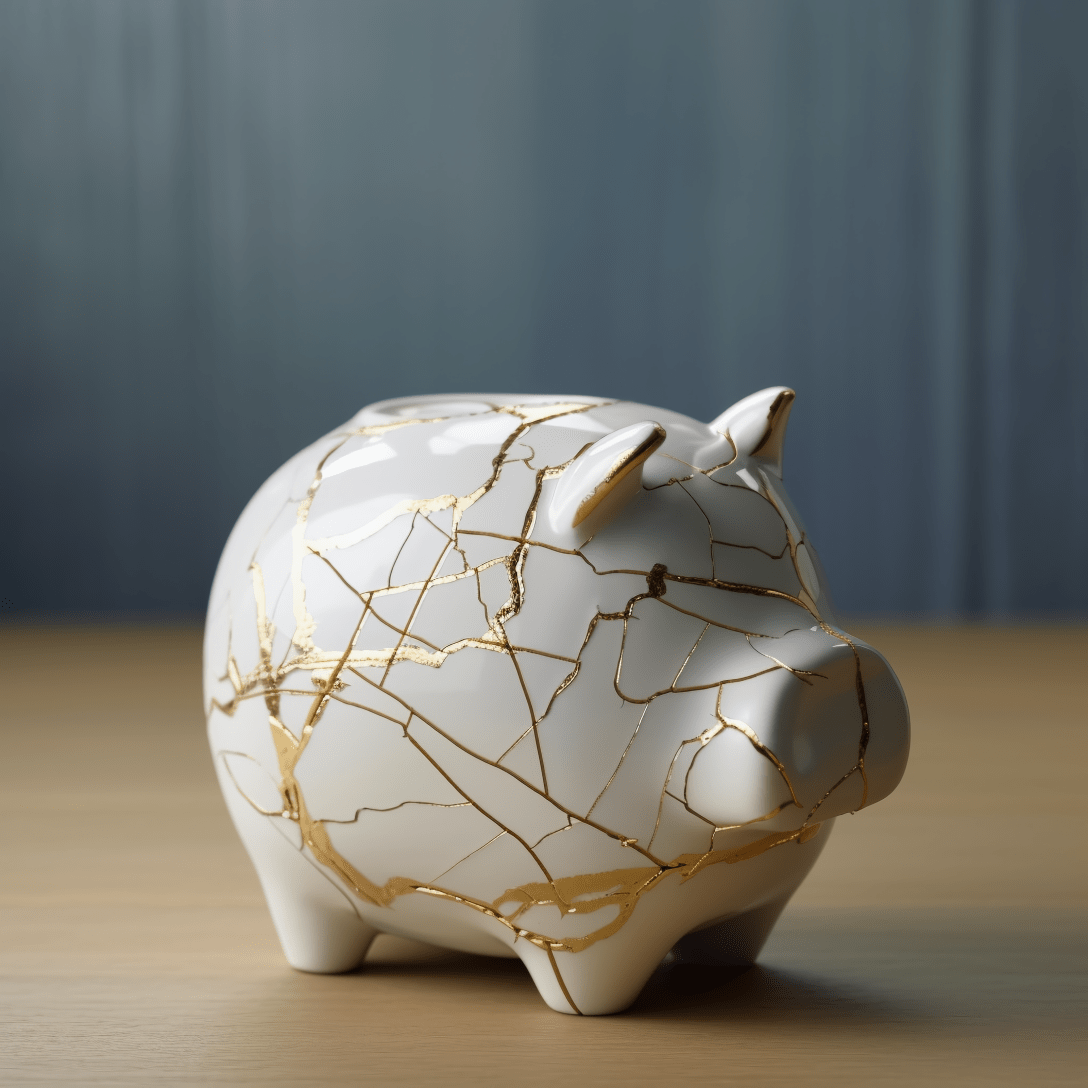

A story of the history of the piggy bank opens the chapter. The ‘kintsugi piggy bank’ is an image from the Kintsugi World art project that is a collaboration between Darinka Montico and myself. We are making some ceramic replicas of the images and will exhibit later in the year. The full set of images can be viewed here.

[i] Robert F. Kennedy challenges Gross Domestic Product. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=77IdKFqXbUY

[ii] Thomson, S. (2016). GDP a poor measure of progress, say Davos economists. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/gdp/

Donate to keep Jem writing / Read his book Breaking Together / Read Jem’s key ideas on collapse / Subscribe to this blog / Study with Jem / Browse his latest posts / Read the Scholars’ Warning / Visit the Deep Adaptation Forum / Receive Jem’s Biannual Bulletin / Receive the Deep Adaptation Review / Watch some of Jem’s talks / Find Emotional Support.

Discover more from Prof Jem Bendell

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Dear Jem Bendell,

I have read most of your new book now and am deeply grateful for it, and

the years of work it is based on. Thank you! Your explanations of ‘how

it is’ have cleared the scales off my eyes at last. I was feeling the

depression and the frustration with how the world is. It is as if I can

now hear from a level above, or behind, the words in the media, more

aware of hidden bias and lies (even in the media I trusted, like the

Guardian!). Most importantly, your ideas of what we might do as we

approach the inevitable collapse are heartening and encouraging. We need

to feel empowered, not helpless.

You have also reminded me of similar positive movements that had the

feeling “We can put this right”, firstly with the Agenda 21 in the ’90s

and then at the start of the Transition movement here in Totnes. They

faded away, unequal to the power of the political/financial status quo

(although many good things do remain from the Transition movement).

I recalled clearly the warm, cheerful, optimistic feeling at the ‘great

unleashing’ of Transition Town Totnes; that we, together, with the

ideas and enthusiasm of local communities, could turn things round. So I

just retrieved some of the writing I did back then, 2006 onwards, about

what to treasure, what to bring back, what to let go of – themes that

you take up now, but for a global audience.

Yes, we do need to talk about this. Yes, and to believe in the

creativity of ordinary people like ourselves.

Thank you so much!

Sincerely,

Susan Hannis

I am pleased to hear you feel re-invigorated to engage locally in reclaiming more of life in Totnes from corporations and elites, creating more locally resilient self-reliant community.

I greatly enjoyed your comments on Davos. I did some research a little while ago and discovered that both Adam Smith and David Ricardo hold that economic growth is necessary to improve the lives of the poorest class in society, the workers. They make it clear that they do not mean merely that the economic pie has to be bigger, but rather that it has to be in a continual state of getting bigger. They give impressive arguments for this thesis, although they only work for the market-type economy they assumed was needed for any growth at all. It seems, then, that the adoration of Economic Growth is more than two hundred years old.