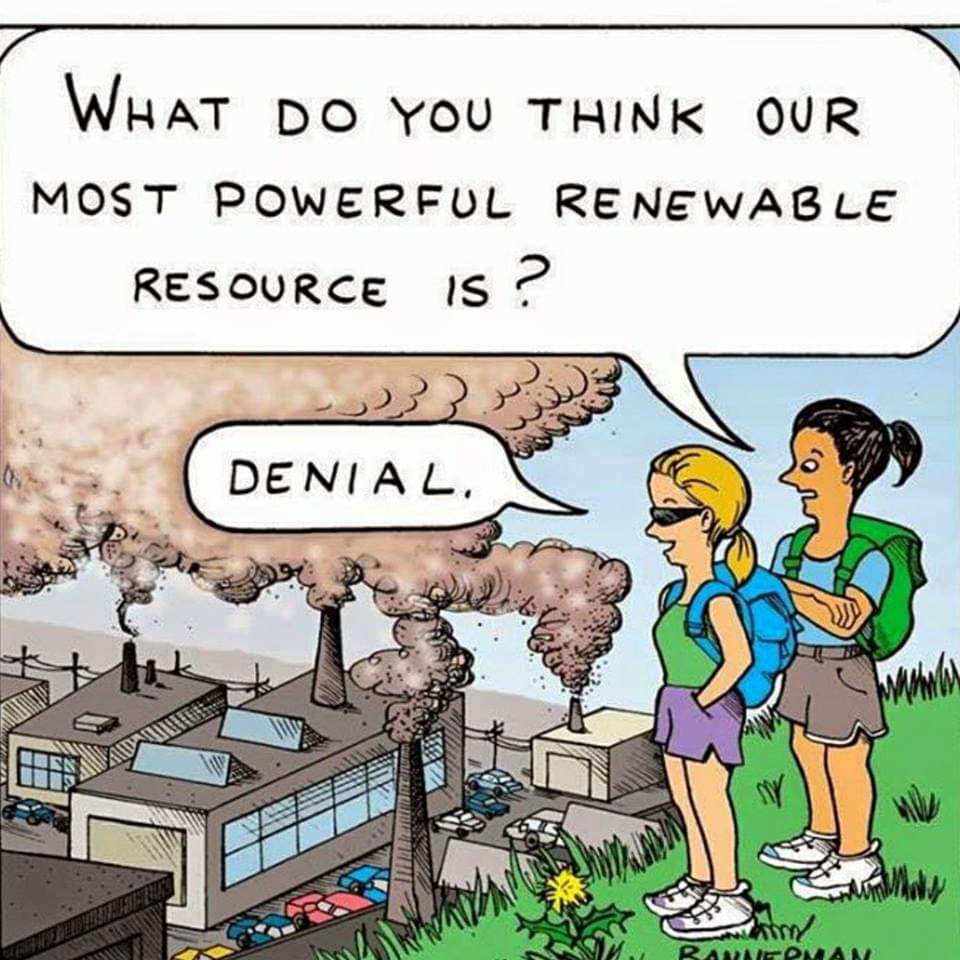

Last week I released a free audio of my chapter on the need for ‘critical wisdom’ in an era of societal disruption and collapse. I linked to it from an essay on a counterproductive phenomenon I refer to as ‘conspiracy porn,’ which has taken off as Big Oil seeks to capture widespread and justified anxieties about regulatory capture and government overreach during the last few years. The outlandish theories about the causes of disasters, promoted through social media, are just the latest efforts of a sector that has spent decades and millions of dollars in promoting denial of climate change (e.g. see here and here). As anxieties grow, people will be more vulnerable to manipulation of all kinds, with both mass media and social media providing avenues for ‘psychological warfare’ on the public by different factions of capital.

So what can we do in response? Unless more of us have an awareness of how the dynamics of capitalist self-interest, and the power elites, are shaping public assumptions and agendas to suit themselves, then we will have our attention drawn away from the key issues and avenues for change. Within sociology, this approach to understanding culture is called ‘critical social theory,’ and within that field, ‘critical discourse analysis.’ As such approaches can help to free us from capitalists and elites shaping our consciousness, it is perhaps no surprise that such approaches are being misrepresented in order to demonise and undermine them. They claim that these ‘critical’ approaches to understanding society are behind the rise of identity politics, cancel culture and ‘wokeism’. However, a critically informed analysis of the rise of those aspects of popular political discourse reveals them to be the outcome of capitalist power relations, not a threat to it.

You can listen to the chapter here or read an excerpt below. As this is such an important skill for these confusing times, I integrate the development of ‘critical wisdom’ in my online courses on Leading Through Collapse.

Subscribe / Support / Study / Essays / Covid

The following is an excerpt from Breaking Together, by Professor Jem Bendell (Good Works, 2023).

As a Professor, when introducing the competence of ‘critical literacy’ to my students, I often explain that a ‘social constructionist’ perspective does not dismiss that there is a reality outside of our socially-influenced perception and conceptualization of that reality. For instance, that perspective does not deny that an iron is hot and will burn us, or that an animal has a biological sex. Rather, it invites us to see how frames, narratives and discourses in society shape how we look for or ignore phenomena, how we then link such phenomena to other phenomena and how we respond emotionally (including physiologically) to such phenomena and the links we construe, in ways that then reproduce patterns in society. Therefore, if we are interested in both personal and collective freedom, we must seek greater awareness of those processes that shape the way we think and feel.

It is obvious that corporations are the biggest storytellers in contemporary societies, through new and old media, advertising and public relations, as well as being donors to politicians and the employers of so many of us. If you still doubt this, then just ask yourself where the tradition for diamond engagement rings came from, and then look into the history of De Beers diamond marketing, or where the tradition of Santa Claus wearing red outfits came from, and then look into Coca Cola advertising. Once realizing the pervasive power of corporations, it is unremarkable to notice that they are serving the interests of capital. Therefore, it is natural to be curious about the ways that capitalism is producing the culture we live within, and how that affects our freedoms.

Compared to other types of scholars, such as economists or computer scientists, contemporary sociologists seem to have had very little influence on society. More often, we sociologists are simply spectators of what is occurring. Even our own interest in analyzing ideology has been brought to mainstream attention by scholars from other disciplines, such as anthropologist Yuval Noah Hariri[i] or cognitive linguist George Lakoff.[ii] That has meant that critical insights into society, particularly the power of capital in shaping culture and politics, have remained fairly marginal in the mainstream. However, with the rise of ‘woke culture’ in Western English-speaking countries in particular, and a backlash to that, suddenly sociology has become a matter of contentious debate and political contestation.

The term ‘woke’ is slang and its meaning is widely contested. I regard it as a particular way of responding to intractable identity-related power differentials in society, which prioritizes that people with perceived privileged identities become aware of their own unconscious biases. The ‘woke’ theory of social change is that through such greater awareness of unconscious bias, myriad changes in interpersonal relations can occur that will shift systemic inequalities. In mainstream media this approach has been associated with a set of ideas called ‘critical race theory’, which in turn has been tenuously connected to ‘critical theory’ in general. One of the main references cited by pundits on these issues in mainstream and alternative media is the book Cynical Theories.[iii]

That book’s authors identify two principles they claim run through the entire body of postmodern thought and, they imply, all of critical social theory. They define a “postmodern knowledge principle” as a radical skepticism about our ability to know objective truths, and a “postmodern political principle” as the belief that “society is formed of systems of power and hierarchies, which decide what can be known and how.” That describes some postmodern theorists but is not an accurate depiction of all critical theory. As described earlier, critical theory is founded on a conviction that an unquestioning receipt of descriptions of reality renders us unfree, not that there is no underlying reality or that some of our descriptions cannot be closer to reality than others. Critical theorists share the conviction that dominant descriptions of reality arise from power relations which those descriptions also help to maintain. Therefore, we have discovered how useful it can be for individuals and groups to explore those power relations with various theories about patterns of power, such as patriarchy, modernity and capitalism. That does not mean power relations are the only lens for understanding the validity of knowledge claims. Rather, critical literacy is one component of a rounded education and sensible approach to understanding society. That is why I include it alongside rationality, mindfulness and intuition within the capability of ‘critical wisdom’. To take any of those components to its extreme, in isolation from the others, would lead to ridiculous views and decisions.[iv]

If you like this analysis, then send it to someone influential, and if you want more, please help fund future writing.

Another critique which might seem relevant to this book and the theory of current collapse is that critical theory is somehow anti-Western or anti-European. However, critical literacy can enable us to deconstruct cultural norms that serve power in, for instance, China and Saudi Arabia as much as in Canada or Australia. The anti-Western claim might therefore indicate a ‘worldview defense’ response from some pundits, as they perceive some aspects of the breakdown of modern societies that is chronicled in this book. That is unfortunate, as critical literacy could help both the proponents and critics of ‘woke’ culture to transcend their current debate into something more useful for positive social change in an era when there is no going back to a prior solidity of cultural cement, as we saw in the previous chapter.

One of the areas where critical literacy could enable insight is the controversy surrounding recent approaches to anti-racism that have been applied in organizations in Western nations. One framing used within such approaches is that racism can only be regarded to exist in someone if they have both prejudice and power. That framing is used by some people to claim that if you identify with a racially oppressed category of identity, then you cannot be racist because your power is insignificant. With critical literacy, it is normal to be curious about whether such binaries about power and identity are enabling or disabling our understanding and mutual liberation from oppression. The first binary is between an identity that has power and an identity that does not have power. The second is the binary between power and no power. However, there are continuums of identities and of types and amounts of power. So, a critical reading can ask in whose interests such binaries are being promoted and with what effects? It can ask how else these categories could be understood. It can ask what economic interests, whether micro-personal ones, or macro-societal ones, are being served by the promotion of such binaries and the stories and behaviors that are built on top of them.

Asking such questions would then put some experiences from anti-racism initiatives in greater context. For instance, in organizations I have experience of, some people who claimed non-white identities believed they did not need to consider their own prejudices and how they might be a barrier to their own healing and contribution. Unfortunately, such racial exceptionalism might allow unethical and unprofessional behaviors to go uncontested. A critically literate perspective would also be sensitive to whether some people might commodify aspects of their racial identity for their own individual advancement. In other words, people understandably seek to have some attention, influence and possibilities for income, and considerations of social justice might mask that aspect of their intent, thereby leading to a lack of reasonable dialogue and accountability. Areas of such commodification of identity include a claim to have a special status due to trauma associated with a particular identity.[v]

The existence of an industry of consultants with a vested interest in promoting ‘woke’ approaches, and of corporations that seek marketing advantage from them, should also raise questions for the critically literate. The fact that some ‘woke’ intellectuals have gained some influence in Western societies could be an indicator of the suitability of their ideas for incorporation into, and defense of, capitalism. And the seductiveness of their ideas to some middle-class professionals could then invite deeper analysis of trends in society related to capitalism. For instance, middle class professionals have been schooled in individualism and consumerism, rather than class struggle, to obtain and secure their livelihoods and lifestyles. Centre left and left politics are widely recognized to have therefore drifted away from solidarity around mutual interests to become about expression of identity. In other words, people consume their politics like they consume their musical tastes. Since at least 2016, such middle classes across the West have been experiencing a systematic decline in their quality of life and future expectations (as I outline in Chapter 1 of Breaking Together). This challenges their sense of self, part of which is being a respectable person on the side of positive change. Living in solidarity with people on the grounds of racial differences is something that can be added to one’s self-expression and sense of moral personhood. One can post socially progressive ideas on social media, and it doesn’t cost anything. However, becoming active in economic equality, involving collaboration and solidarity with the working classes to challenge power, is more complicated. When working on racial solidarity, a white middle class person isn’t expected to change their racial identity, because they can’t. However, if working on economic solidarity, why would such a person not share their surplus wealth with someone of lower economic status? It’s an obvious question, and it comes up in any worker-solidarity movement. Therefore, we could regard the rise of identity politics amongst middle classes on the left as part of their abandonment of a more substantive solidarity. With woke culture, capitalism could be seen as offering middle class people chances to momentarily alleviate their anxiety from their declining standard of living, lost opportunities and a meaning crisis, by pursuing matters other than economic equality and the need for the slow and difficult process of broad-based solidarity against capitalists.

Further critical theoretical analysis might explore whether ‘woke’ anti-racist approaches are disrupting existing challenges to capitalism, such as radical environmental, human rights and anti-war movements. If woke approaches preoccupy some white people in those movements due to a desire to be the most ‘ethical’ they can be (and be seen to be) without any loss of their privilege and power, while also paralyzing other white people in those movements due to a fear of shame, and triggering internal conflict and division, then that would undermine the effectiveness of those movements.

It is only with critical wisdom that a comprehensive critique could be offered of ‘woke’ anti-racism approaches as having commodified our desires for social justice into a competence that white-racialized people learn at work, consultants earn a living from, managers use to threaten workers, brands use to promote themselves and infiltrators use to paralyze movements that challenge corporate power, while very few people of color have their lives improved from the process, especially not the economically marginalized. But it is also only with critical wisdom that we could entertain such critiques while continuing to seek mutual liberation from the oppressions that operate through language and culture. Without it, we might fall back entirely on the liberal approaches to social injustices that have done so little to change the economic experience of people with identities associated with economic disadvantage. A critical perspective would encourage the ‘woke’ to explore how to avoid divisions that serve the status quo, and build solidarity towards challenging corporate power in ways that serve people of any identity. My application of critical literacy to constructively question the frameworks of woke approaches to anti-racism hopefully demonstrates that the problem with those approaches does not condemn the whole of critical social theory. Instead, the opposite is true—if critical literacy was more widespread, those approaches might not have spread uncontested and unrefined.[vi]

Breaking Together: A freedom-loving response to collapse

Donate to keep Jem writing / Read his book Breaking Together / Read Jem’s key ideas on collapse / Subscribe to this blog / Study with Jem / Browse his latest posts / Read the Scholars’ Warning / Visit the Deep Adaptation Forum / Receive Jem’s Biannual Bulletin / Receive the Deep Adaptation Review / Watch some of Jem’s talks / Find Emotional Support / Jem’s actual views on Covid

[i] Harari, Y. N. (2011). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Vintage.

[ii] Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate: The Essential Guide for Progressives. Chelsea Green Publishing.

[iii] Pluckrose, H. & Lindsay, J. (2020). Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody. Pitchstone Publishing.

[iv] Although many of the proponents of critical approaches to education believe that our mutual liberation is an aim which is constantly under threat from hierarchical power and will never be complete, that is not our sole interest.

[v] Sometimes that can include a claim to carry an ancestral trauma through their DNA, family heritage and identity. That inherited trauma theory is questionable due to arbitrary boundaries about which ancestors matter to one’s current experience, and ignores that if one goes far enough back in history, nearly every oppressed racial group can also be identified to have once been an oppressing group.

[vi] An additional quick comment on the term ‘Cultural Marxism’ which has become popular amongst critics of woke culture may be helpful here. They use it to describe an agenda that wants to see divisions between identity groups accentuated, to enable identity struggles, that might then reduce the power of privileged identities. The similarities with Marxism are the idea of differentiation, struggle and a zero sum perspective on power. However, that is where the similarities end. Marxist analysis has critiqued a focus on identity struggles as a way of dividing and confusing the economic classes which do not own capital. Therefore, there is little authentic Marxist underpinning of the ideas being labelled as ‘Cultural Marxism’ and the term is popular mainly because it sounds like it something both intellectually robust (it isn’t) and dangerous.