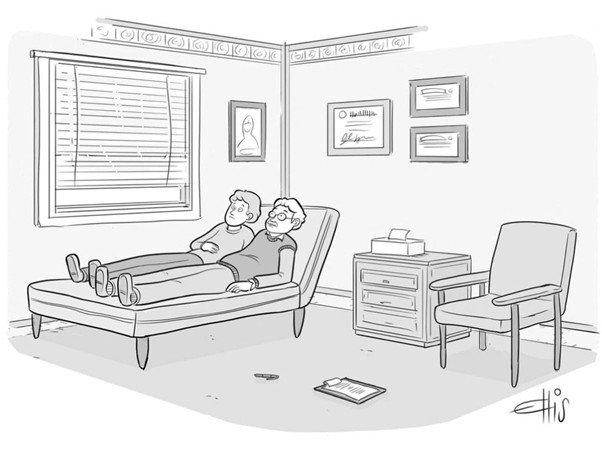

I invited the co-admin of the largest Deep Adaptation group in the world to share her ideas on the difficult emotions experienced by people who awaken to metacrisis and collapse. In this essay Krisztina Csapo explains it is unhelpful to frame such emotions as a form of general anxiety. Instead, more can be gained from recognising and responding to them as dread, grief, trauma and moral injury. I have left comments open for you to share relevant resources and initiatives at the end. Thx, Jem (Image by Ellis Rosen).

How do we psychologically sustain ourselves in times like these? This question arises again and again within communities working on ecological and social harm, and especially on the prospect of societal collapse. Through six years of engagement with the international Deep Adaptation movement, including facilitating the largest such national group, I have become much clearer about what helps — and what does not. That clarity begins with taking seriously the emotional reality people are living with as they confront the full gravity of our predicament.

I have come to see that framing what people — especially young people — are feeling as “climate anxiety” is often a misdiagnosis. It is misleading because it suggests a variant of generalized anxiety, thereby pathologizing responses that are understandable and proportionate to the situation. And it is unhelpful because well-known anxiety-management strategies frequently fail to address the deeper distress involved, sometimes adding shame or a sense of inadequacy when the “anxiety” does not go away.

When I joined the international and Hungarian Deep Adaptation Facebook groups in the summer of 2019, what I encountered was not primarily anxiety, but existential dread: a profound, often paralyzing apprehension of a catastrophic future that feels both inevitable and beyond individual control. This was not a free-floating unease, but a rational response to converging trajectories of ecological collapse, social unraveling, and political inadequacy. It closely resembles what has been described as pre-traumatic stress — the lived experience of anticipating further harm that has already begun.

Although trauma frameworks have been present in the new field of ‘climate psychology’ for more than a decade, they have not become central within mainstream psychological discourse. ‘Climate trauma’ is still most commonly understood as the psychological aftermath of climate-related disasters, often framed in terms of PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder). Yet a growing body of research suggests that for some people, the mere awareness of the scale, severity, and inevitability of climate breakdown can itself be traumatizing. This awareness can shatter a person’s sense of safety, continuity, and future, reaching into intimate life decisions: education and career paths, whether to have children, and where it feels possible — or ethical — to build a life. These themes arise repeatedly in Deep Adaptation groups, DA Clubs, and the climate grief groups I facilitate.

At a deeper level, this rupture can be understood as the loss of what trauma theorists call the assumptive world: the taken-for-granted beliefs that the world is predictable, that effort leads to reward, and that the future can be meaningfully shaped. As these assumptions fracture, people often experience not only distress, but a profound loss of meaning, identity, and moral orientation. Long-held narratives about who I am, what matters, and what kind of life is worth striving for begin to fall apart.

Alongside dread, another recurring theme I encounter can be termed ‘moral injury’: the deep existential wound that arises from witnessing, participating in, or feeling complicit within systems that cause profound harm while betraying core values. This includes the anguish of knowing that one’s own society — and often one’s own way of life — contributes to ecological destruction, alongside feelings of guilt, shame, anger, and helplessness.

To frame these experiences primarily as anxiety risks minimizing and invalidating them. Dread, trauma, and moral injury do not metabolize into action in the same way anxiety can do. Anxiety, as it is usually understood in psychology, presupposes uncertainty and the possibility that threat can be avoided through appropriate action. However, dread emerges when harm is no longer hypothetical, when it is already underway, and when the systems meant to offer protection are themselves implicated. It is not a signal to act more efficiently, but a response to the erosion of fundamental assumptions about safety, progress, and continuity.

Attempts to “convert” dread into action often misrecognize what is actually being expressed. They can unintentionally reproduce the very dynamics that generate distress in the first place: urgency without agency, responsibility without power, and emotional labour without structural change. In this sense, dread is not a failure of coping or motivation, but an understandable and appropriate response to living within a metacrisis — one that exceeds the behavioural and cognitive frames through which psychology, and the psychotherapy profession, have often tried to contain it.

Much of what is currently described as climate anxiety, along with many proposed interventions, remains situated at the level of what is termed a ‘polycrisis’. These approaches address the symptoms of overlapping ecological, social, and political breakdowns, without engaging the deeper question of why the foundations of our civilization are unraveling in the first place. I prefer the term metacrisis for our predicament, as it points to the underlying conditions: extractive economic dynamics, severed relationships with the living world, social structures that demand our compliance with what is unsustainable, and, now, the fracturing of our meaning-making systems. From this perspective, dread is not something to be resolved so that “normal functioning” can resume — especially when “normal” itself is part of the problem.

Here, a climate trauma framework is helpful for our understanding and focus. One view is that the destruction of our biosphere and the inability to respond sufficiently at scale, derives from the collective trauma which so many of us experienced from growing up in cultures that separated our consciousness from the living world and instilled a deep sense of insecurity. Additional to that, climate chaos can be recognised as causing a form of collective trauma of its own. That offers us a way to understand climate-related emotions not as individual pathologies, but as responses to an unprecedented, ongoing threat that calls into question what it means to be human. It is here that the work of Zhiwa Woodbury offers a crucial reframing. As he writes:

“When viewed honestly through the lens of traumatology, this deepening existential crisis presents an entirely new, unprecedented, and higher-order category of trauma: Climate Trauma. What is unique about this category of trauma is that it is an ever-present, ever-growing threat to the biosphere, one that calls into question our shared identity… Because it is superordinate, Climate Trauma continually activates all past traumas — personal, cultural, and intergenerational — and will continue to do so until it is fully acknowledged.”

Seen this way, climate-related distress is not simply an accumulation of stressors, nor a failure of resilience or coping. It reflects the psychological impact of living within a condition that destabilizes identity, meaning, and moral orientation at their roots.

Viewed through this lens, the guiding question shifts from how to manage distress to how to support deeper processes of healing — at individual, communal, and collective levels. Rather than asking how to reduce uncomfortable feelings, this framework opens space for grief, reorientation, and the slow work of rebuilding meaning in a world where old certainties no longer hold. What we are facing is not merely a psychological challenge, but a collective threshold experience: a liminal time in which familiar systems of meaning are breaking down and new ones have not yet come into being.

For me, healing in this context unfolds through shared processes of truth-telling and grief — allowing losses to be witnessed rather than dissociated from. When I joined the Deep Adaptation groups, alongside the many expressions of fear, it was grief that members most frequently shared, even if they did not use that word. What surfaced instead were feelings connected to multiple kinds of loss: ecosystems being destroyed; relationships strained or broken when friends or family could not understand their concerns or values; and the erosion of trust in social and political systems meant to offer protection.

People were not only grieving what had already been lost. Much of what was expressed was grief for losses still unfolding or widely expected to unfold — what is more accurately described as anticipatory grief, a process well known in contexts such as terminal illness. This is where the concept of eco-anxiety often becomes misleading. When losses are highly probable or structurally embedded, the dominant emotional process is not uncertainty-driven anxiety but grief. To frame anticipatory grief as anxiety is a categorical error, much like describing dread as anxiety.

Another deeply destabilizing form of loss also emerged repeatedly: the loss of the image of a viable future. People spoke about losing sight of the future — lives, hopes, and trajectories that had quietly structured meaning and motivation. What was being expressed was not simply fear of uncertainty, but the collapse of a future that once provided orientation and purpose.

After my husband’s sudden death, I went through a strikingly similar process at a personal level, grieving not only the loss of a loved one but the loss of a future that could no longer unfold as I had imagined. Years later, I began to perceive the same psychological pattern emerging collectively, even without a single identifiable event. Unlike the grief for a loved one, with climate, the loss of an image of the future often becomes primary rather than secondary: the disappearance of assumed possibilities, inherited narratives of progress and safety, and familiar ways of being human. That absence can be profoundly disorienting and traumatic in itself.

When a future worth striving toward collapses, loss of meaning and motivation often follows. Past efforts can come to feel pointless, and the present becomes something to be endured rather than lived toward. This is not anxiety about what might happen, but grief for what will no longer be possible — often accompanied by imagined futures filled not with hope, but with nightmares. As long as we remain attached to what could have been, movement toward any other possible future remains blocked.

Grief, in this sense, becomes a passage between worlds. This understanding was already present in the original Deep Adaptation paper, which invited readers to step back, consider “what if” the analysis is true, allow themselves to grieve, and find meaning in new ways of being and acting. The Deep Adaptation agenda itself is deliberately simple: three guiding values — compassion, respect, and curiosity — and four questions that offer a shared language for staying present within this liminal terrain, rather than prescribing answers.

For me, Deep Adaptation embodies a form of lay spirituality. Not a belief system or an escape from reality, but a way of orienting oneself when familiar sources of meaning, certainty, and control have fallen away. One definition of spirituality I return to describes it as being the best human being possible. In this sense, spirituality is not about transcendence, but about how we choose to live, relate, and take responsibility amid loss and limits. It is this form of spirituality which I have become convinced is key to how we might positively respond to the experiences of dread, trauma, grief and moral injury in relation to environmental and climate chaos.

At its core, every spiritual inquiry involves questions of identity: Who am I? What does it mean to be human? These are precisely the questions grief brings into focus. As losses accumulate, familiar identities unravel. Roles, aspirations, and self-understandings no longer hold, often resulting in a kind of personal collapse in which what is lost is not only external, but internal. In this sense, spirituality is not an escape from pain or reality, but a deepening of presence and belonging: as Joanna Macy reminded us, learning to stay with grief and dread can become a doorway into remembering our true identity as living members of a living Earth, rather than separate selves standing apart from it. From this perspective, healing from climate trauma is inseparable from an existential and spiritual inquiry — one that does not seek definitive answers, but learns how to remain present with what hurts, what matters, and what calls for care. In the words of Reverend Stephen Wright: our deep adaptation will be spiritual, or not at all.

This process, however, can be obstructed by both professional and spiritual forms of bypass. Such bypass often arises mostly from overwhelm. When the emotional and existential weight of the crisis exceeds what individuals or cultures feel able to bear, there is a strong pull to move away from pain — into techniques, diagnoses, or transcendent narratives. Psychological language can be used to contain what is actually a deeper wound; spiritual language can offer reassurance or distance where presence is needed. Yet grief cannot be bypassed without cost. Even when unrecognized, it continues to move through its own logic — appearing as denial, anger, bargaining, depression, or emotional numbing — asking to be acknowledged and held rather than managed away.

It is also important to recognize that these dynamics are not universal. Much of what I describe reflects the experience of dominant, industrialized, and relatively privileged societies, where assumptions of stability and progress have long gone unquestioned. For many Indigenous communities, people in war zones, or those already living with the impacts of climate breakdown, loss and uncertainty are not emerging realities but long-standing conditions. In these contexts, climate trauma may be experienced less as the collapse of an imagined future and more as the continuation of historical and structural harm.

At the same time, the more privileged populations form the psychological and economic backbone of a dominant global system, described as Imperial Modernity by Professor Jem Bendell in his book Breaking Together. Consumer societies and growth-based economies depend on their continued motivation and belief in a viable future. When that future unravels at an existential level, the effects reverberate far beyond individual distress. For this reason, engaging seriously with grief and trauma in these contexts is not a distraction from justice, but one of the places where systemic change may either be resisted — or become possible.

What is at stake, then, is our willingness to stay with what is being revealed. Dread, grief, and the loss of meaning are part of how this moment makes itself felt in human lives. They point to the depth of the rupture we are living through, and to the limits of the frameworks that once helped us make sense of the world.

Working with climate trauma does not bring resolution or closure. It asks for attention, honesty, and the capacity to remain in relationship with what hurts and what matters. Meaning is not restored all at once, but slowly reshaped through how we listen, how we respond, and how we take responsibility for one another and for the living world.

How we sustain ourselves in times like these may begin here: by allowing the difficult emotions of this moment to be understood and held, rather than explained away or hurried past. I am glad that the Metacrisis Meetings Initiative is creating space for this kind of attention, and I look forward to continuing the conversation together at the online salon in March.

Krisztina Csapo

—

Follow the links below to register for the March salon, or the February Salon, where we will explore the challenge of reclaiming environmentalism. Feel free to leave a comment below on relevant resources and initiatives.

—

Join the MMI to discuss with us live

Dread, Grief & God in the Metacrisis: MMI 7

We will share our ideas on allowing and integrating difficult emotions in response to experiences of damage and disruption, plus awareness of future loss and breakdown. We will discuss the benefit of framing these emotion in terms of dread, grief, trauma, and moral injury, rather than anxiety, and the role of community and spirituality in how we cope or even thrive in the metacrisis. We will be joined by Krisztina Csapo, co-administrator of the largest Deep Adaptation group in the world. Register in advance for this meeting:

Time Option 1: March 2nd 10:00AM London, 11:00AM Paris/Budapest, 3:30PM New Delhi, 6:00PM Kuala Lumpur, 9:00PM Sydney.

Time Option 2 March 3:00PM San Francisco, 6:00PM New York, 8:00PM Santiago / and Tuesday Feb 3rd 7:00AM Kuala Lumpur, 10:00AM Sydney.

Discover more from Prof Jem Bendell

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Grief for sure. Absolutely. Me too and forever. And a metacrisis. And being a metacrisis it has a primary root cause, which is the disruption of our evolution by overpopulation by humans, and having a human cause it is both preventable and curable by humans. Instead we continue to use it to make money, where in fact we could have, in my lifetime, begun to prevent and cure.

Thanks for the “spiritual Inquiry”, dear Jem.

I am engaged in your work since the beginning and appreciate it!

Your article reminds me of Paul Tillichs: “Courage to Be”

We wrote about it in our blog “Metameaning”

https://metameaning.com/en/present-and-history-en/paul-tillich-the-courage-to-be/

And in the corresponding podcast.

with appreciation

Josef and Simone

as Greta Thunberg voiced some time ago, and coming from a child’s/teenager perspective, enough blah . Blah , blah.

what concrete actions are needed to change predicaments to problem analyses and resolve Kent’s?

what is it in human nature, and subsequent ways of living, which needs to be changed? Which actions are needed to reduce the consumption of natural environments? Can we exist with 8 or 9 billion humans living as we do, and if yes, how.. if not, how can we change that potential condition which will lead to Greta’s understanding of what we are saying?? What are the blah Noah’s?

I tried… but the problems associated with cyber life intervened…

A brilliant article! I’m sharing it widely.