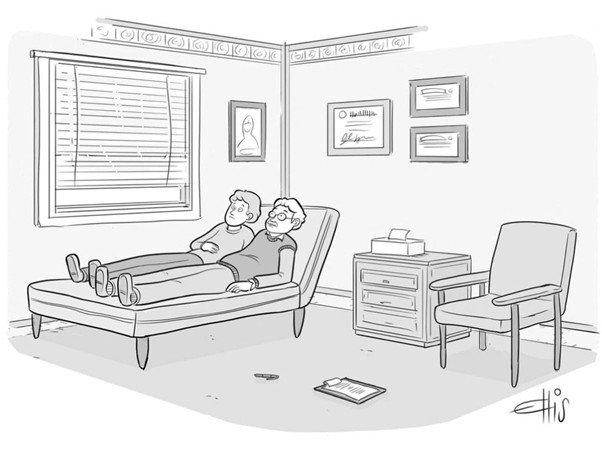

I invited the co-admin of the largest Deep Adaptation group in the world to share her ideas on the difficult emotions experienced by people who awaken to metacrisis and collapse. In this essay Krisztina Csapo explains it is unhelpful to frame such emotions as a form of general anxiety. Instead, more can be gained from recognising and responding to them as dread, grief, trauma and moral injury. I have left comments open for you to share relevant resources and initiatives at the end. Thx, Jem (Image by Ellis Rosen).

How do we psychologically sustain ourselves in times like these? This question arises again and again within communities working on ecological and social harm, and especially on the prospect of societal collapse. Through six years of engagement with the international Deep Adaptation movement, including facilitating the largest such national group, I have become much clearer about what helps — and what does not. That clarity begins with taking seriously the emotional reality people are living with as they confront the full gravity of our predicament.

I have come to see that framing what people — especially young people — are feeling as “climate anxiety” is often a misdiagnosis. It is misleading because it suggests a variant of generalized anxiety, thereby pathologizing responses that are understandable and proportionate to the situation. And it is unhelpful because well-known anxiety-management strategies frequently fail to address the deeper distress involved, sometimes adding shame or a sense of inadequacy when the “anxiety” does not go away.

Continue reading “Don’t Forget the Dread – Deeper Healing in the Metacrisis”